A sophisticated AitM-enabled implant evolving since 2005

ESET researchers provide an analysis of an attack carried out by a previously undisclosed China-aligned threat actor we have named Blackwood, and that we believe has been operating since at least 2018. The attackers deliver a sophisticated implant, which we named NSPX30, through adversary-in-the-middle (AitM) attacks hijacking update requests from legitimate software.

Key points in this blogpost:

- We discovered the NSPX30 implant being deployed via the update mechanisms of legitimate software such as Tencent QQ, WPS Office, and Sogou Pinyin.

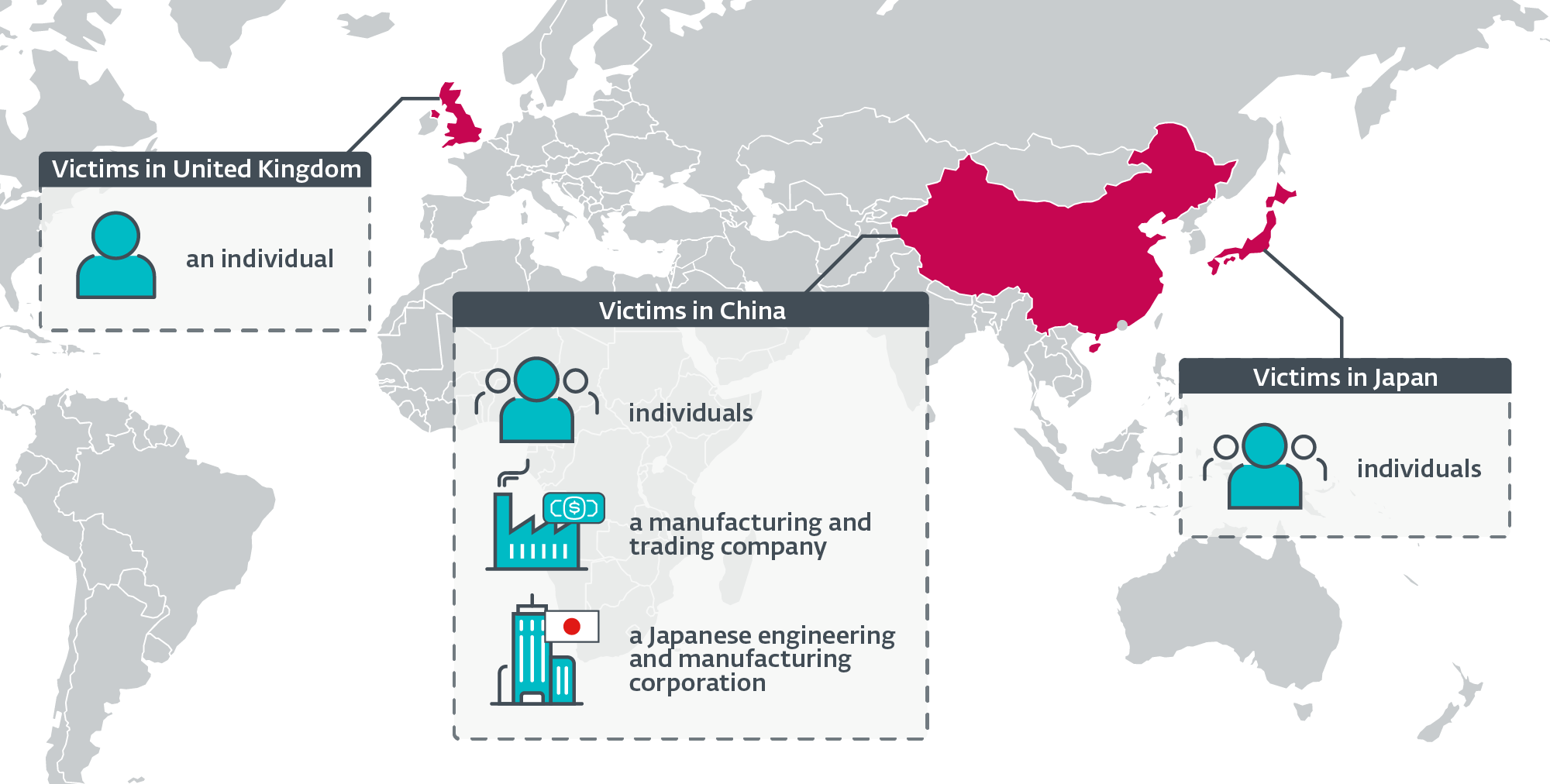

- We have detected the implant in targeted attacks against Chinese and Japanese companies, as well as against individuals located in China, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

- Our research traced the evolution of NSPX30 back to a small backdoor from 2005 that we have named Project Wood, designed to collect data from its victims.

- NSPX30 is a multistage implant that includes several components such as a dropper, an installer, loaders, an orchestrator, and a backdoor. Both of the latter two have their own sets of plugins.

- The implant was designed around the attackers’ capability to conduct packet interception, enabling NSPX30 operators to hide their infrastructure.

- NSPX30 is also capable of allowlisting itself in several Chinese antimalware solutions.

- We attribute this activity to a new APT group that we have named Blackwood.

Blackwood Profile

Blackwood is a China-aligned APT group active since at least 2018, engaging in cyberespionage operations against Chinese and Japanese individuals and companies. Blackwood has capabilities to conduct adversary-in-the-middle attacks to deliver the implant we named NSPX30 through updates of legitimate software, and to hide the location of its command and control servers by intercepting traffic generated by the implant.

Campaign overview

In 2020, a surge of malicious activity was detected on a targeted system located in China. The machine had become what we commonly refer to as a “threat magnet”, as we detected attempts by attackers to use malware toolkits associated with different APT groups: Evasive Panda, LuoYu, and a third threat actor we track as LittleBear.

On that system we also detected suspicious files that did not belong to the toolkits of those three groups. This led us to start an investigation into an implant we named NSPX30; we were able to trace its evolution all the way back to 2005.

According to ESET telemetry, the implant was detected on a small number of systems. The victims include:

- unidentified individuals located in China and Japan,

- an unidentified Chinese-speaking individual connected to the network of a high-profile public research university in the United Kingdom,

- a large manufacturing and trading company in China, and

- the office in China of a Japanese corporation in the engineering and manufacturing vertical.

We have also observed that the attackers attempt to re-compromise systems if access is lost.

Figure 1 is a geographical distribution of Blackwood’s targets, according to ESET telemetry.

NSPX30 evolution

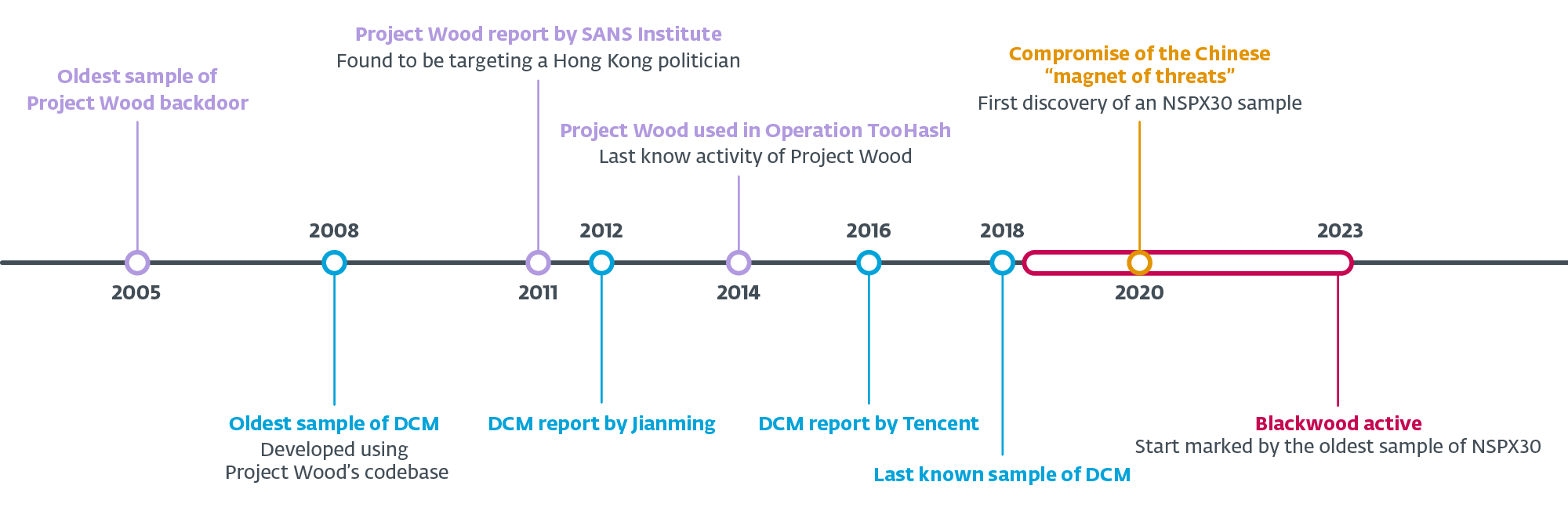

During our research into the NSPX30 implant, we mapped its evolution back to an early ancestor – a simple backdoor we’ve named Project Wood. The oldest sample of Project Wood we could find was compiled in 2005, and it seems to have been used as the codebase to create several implants. One such implant, from which NSPX30 evolved, was named DCM by its authors in 2008.

Figure 2 illustrates a timeline of these developments, based on our analysis of samples in our collection and ESET telemetry, as well as public documentation. However, the events and data documented here are still an incomplete picture of almost two decades of development and malicious activity by an unknown number of threat actors.

In the following sections we describe some of our findings regarding Project Wood, DCM, and NSPX30.

Project Wood

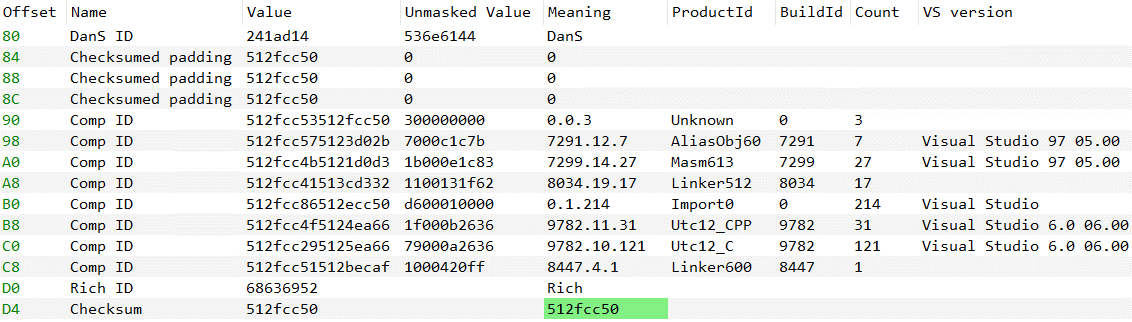

The starting point in the evolution of these implants is a small backdoor compiled on January 9th, 2005, according to the timestamps present in the PE header of its two components – the loader and the backdoor. The latter has capabilities to collect system and network information, as well as to record keystrokes and take screenshots.

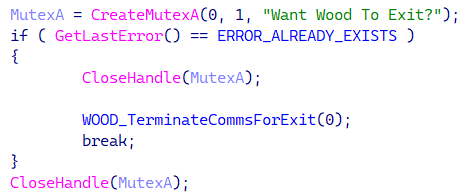

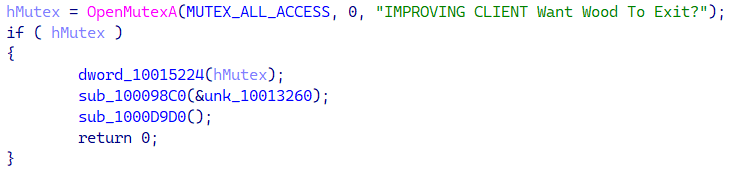

We named the backdoor Project Wood, based on a recurring mutex name, as shown in Figure 3.

Compilation timestamps are unreliable indicators, as they can be tampered by attackers; therefore, in this specific case, we considered additional data points. First, the timestamps from the PE header of the loader and backdoor samples; see Table 1. There is only a difference of 17 seconds in the compilation time of both components.

Table 1. PE compilation timestamps in components from the 2005 sample

|

SHA-1 |

Filename |

PE compilation timestamp |

Description |

|

9A1B575BCA0DC969B134 |

MainFuncOften.dll |

2005-01-09 08:21:22 |

Project Wood backdoor. The timestamp from the Export Table matches the PE compilation timestamp. |

|

834EAB42383E171DD6A4 |

N/A |

2005-01-09 08:21:39 |

The Project Wood loader contains the backdoor embedded as a resource. |

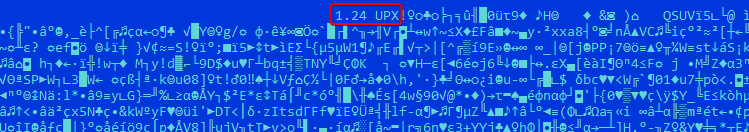

The second data point comes from the dropper sample that was compressed using UPX. This tool inserts its version (Figure 4) into the resulting compressed file – in this case, UPX version 1.24, which was released in 2003, prior to the compilation date of the sample.

The third data point is the valid metadata from the PE Rich Headers (Figure 5) which indicate that the sample was compiled using Visual Studio 6.0, released in 1998, prior to the sample’s compilation date.

We assess that it is unlikely that the timestamps, Rich Headers metadata, and UPX version were all manipulated by the attackers.

Public documentation

According to a technical paper published by the SANS Institute on September 2011, an unnamed and unattributed backdoor (Project Wood) was used to target a political figure from Hong Kong via spearphishing emails.

In October 2014, G DATA published a report of a campaign it named Operation TooHash, which has since been attributed to the Gelsemium APT group. The rootkit G DATA named DirectsX loads a variant of the Project Wood backdoor (see Figure 6) with some features seen in DCM and later in NSPX30, such as allowlisting itself in cybersecurity products (detailed later, in Table 4).

DCM aka Dark Specter

The early Project Wood served as a codebase for several projects; one of them is an implant called DCM (see Figure 7) by its authors.

The report from Tencent in 2016 describes a more developed DCM variant that relies on the AitM capabilities of the attackers to compromise its victims by delivering the DCM installer as a software update, and to exfiltrate data via DNS requests to legitimate servers. The last time that we observed DCM used in an attack was in 2018.

Public documentation

DCM was first documented by the Chinese company Jiangmin in 2012, although it was left unnamed at that point, and was later named Dark Specter by Tencent in 2016.

NSPX30

The oldest sample of NSPX30 that we have found was compiled on June 6th, 2018. NSPX30 has a different component configuration than DCM because its operation has been divided into two stages, relying fully on the attacker’s AitM capability. DCM’s code was split into smaller components.

We named the implant after PDB paths found in plugin samples:

- Z:\Workspace\mm\32\NSPX30\Plugins\plugin\b001.pdb

- Z:\Workspace\Code\MM\X30Pro\trunk\MM\Plugins\hookdll\Release\hookdll.pdb

We believe that NSP refers to its persistence technique: the persistent loader DLL, which on disk is named msnsp.dll, is internally named mynsp.dll (according to the Export Table data), probably because it is installed as a Winsock namespace provider (NSP).

Finally, to the best of our knowledge, NSPX30 has not been publicly documented prior to this publication.

Technical analysis

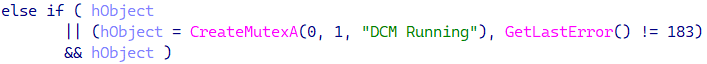

Using ESET telemetry, we determined that machines are compromised when legitimate software attempts to download updates from legitimate servers using the (unencrypted) HTTP protocol. Hijacked software updates include those for popular Chinese software such as Tencent QQ, Sogou Pinyin, and WPS Office.

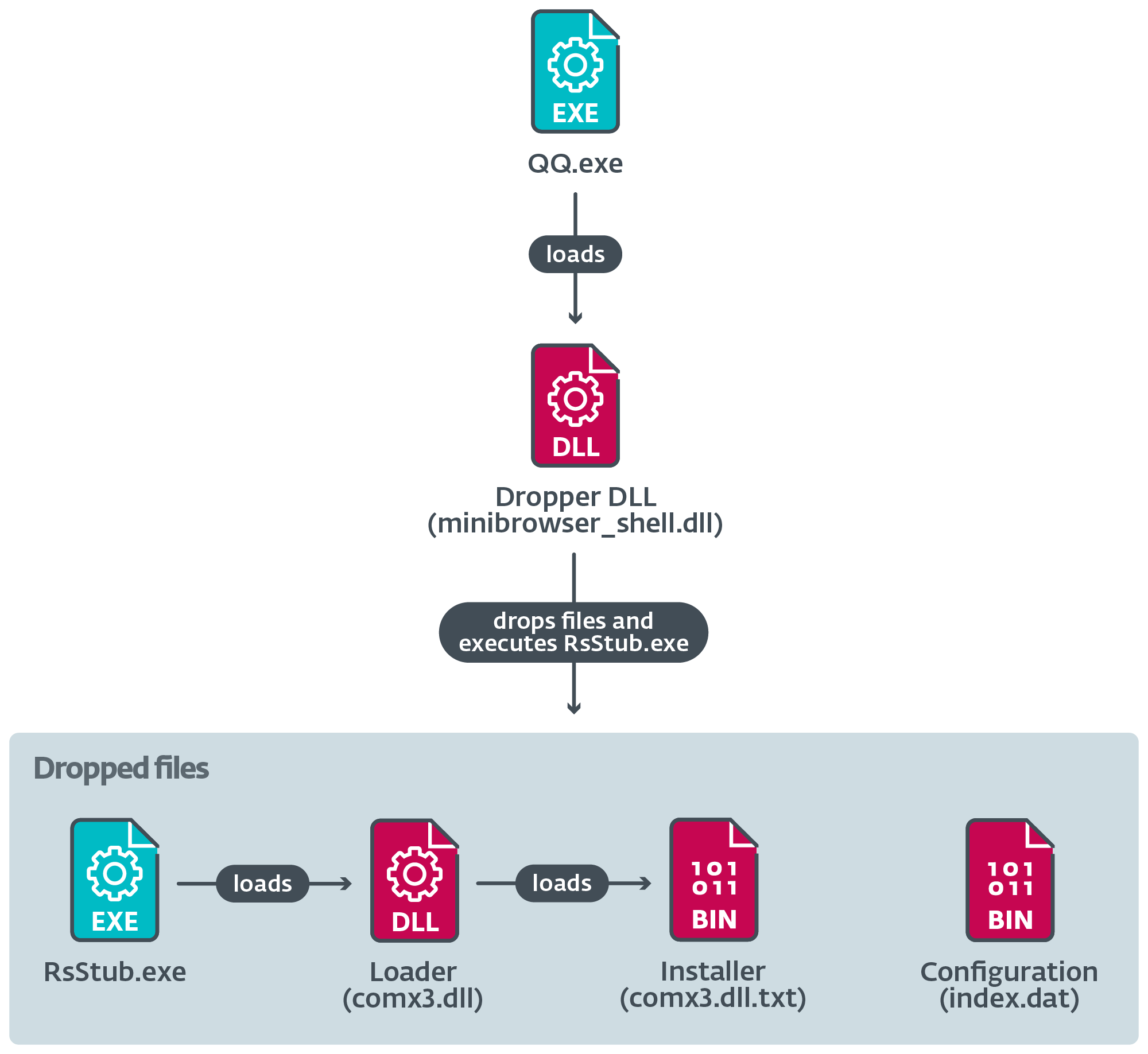

An illustration of the chain of execution as seen in ESET telemetry is shown in Figure 8.

In Table 2, we provide an example of a URL and the IP address to which the domain was resolved on the user’s system at the time the download occurred.

Table 2. An observed URL, server IP address, and process name of a legitimate downloader component

|

URL |

First seen |

IP address |

ASN |

Downloader |

|

http://dl_dir.qq[.]com/ |

2021‑10‑17 |

183.134.93[.]171 |

AS58461 (CHINANET) |

Tencentdl.exe |

According to ESET telemetry and passive DNS information, the IP addresses that observed on other cases, are associated with domains from legitimate software companies; we have registered up to millions of connections on some of them, and we have seen legitimate software components being downloaded from those IP addresses.

Network implant hypothesis

How exactly the attackers are able to deliver NSPX30 as malicious updates remains unknown to us, as we have yet to discover the tool that enables the attackers to compromise their targets initially.

Based on our own experience with China-aligned threat actors that exhibit these capabilities (Evasive Panda and TheWizards), as well as recent research on router implants attributed to BlackTech and Camaro Dragon (aka Mustang Panda), we speculate that the attackers are deploying a network implant in the networks of the victims, possibly on vulnerable network appliances such as routers or gateways.

The fact that we found no indications of traffic redirection via DNS might indicate that when the hypothesized network implant intercepts unencrypted HTTP traffic related to updates, it replies with the NSPX30 implant’s dropper in the form of a DLL, an executable file, or a ZIP archive containing the DLL.

Previously, we mentioned that the NSPX30 implant uses the packet interception capability of the attackers in order to anonymize its C&C infrastructure. In the following subsections we will describe how they do this.

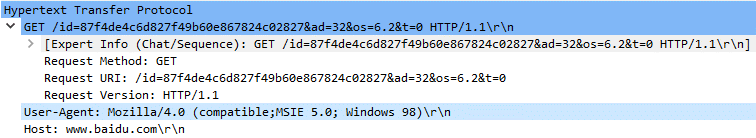

HTTP interception

To download the backdoor, the orchestrator performs an HTTP request (Figure 9) to the Baidu’s website – a legitimate Chinese search engine and software provider – with a peculiar User-Agent masquerading as Internet Explorer on Windows 98. The response from the server is saved to a file from which the backdoor component is extracted and loaded into memory.

The Request-URI is custom and includes information from the orchestrator and the compromised system. In non-intercepted requests, issuing such a request to the legitimate server returns a 404 error code. A similar procedure is used by the backdoor to download plugins, using a slightly different Request-URI.

The network implant would simply need to look for HTTP GET requests to www.baidu.com with that particular old User-Agent and analyze the Request-URI to determine what payload must be sent.

UDP interception

During its initialization, the backdoor creates a passive UDP listening socket and lets the operating system assign the port. There can be complications for attackers using passive backdoors: for instance, if firewalls or routers using NAT prevent incoming communication from outside of the network. Additionally, the controller of the implant needs to know the exact IP address and port of the compromised machine to contact the backdoor.

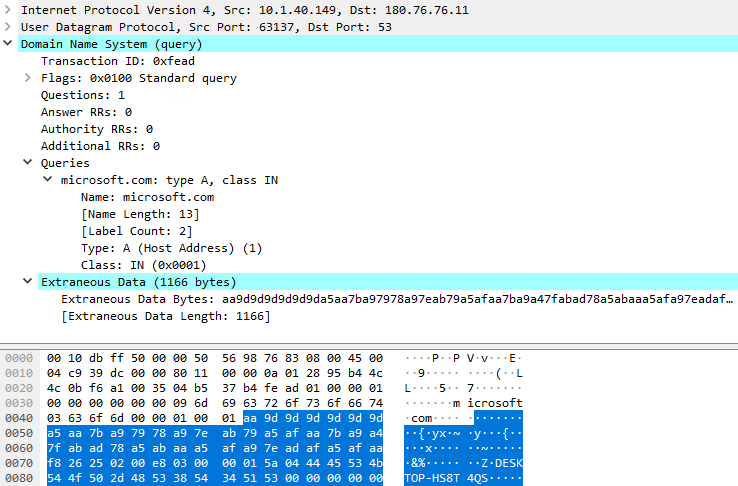

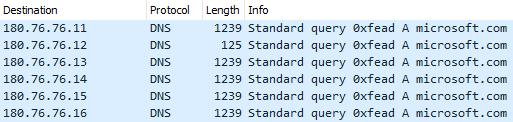

We believe that the attackers solved the latter problem by using the same port on which the backdoor listens for commands to also exfiltrate the collected data, so the network implant will know exactly where to forward the packets. The data exfiltration procedure, by default, begins after the socket has been created, and it consists of DNS queries for the microsoft.com domain; the collected data is appended to the DNS packet. Figure 10 shows a capture of the first DNS query sent by the backdoor.

The first DNS query is sent to 180.76.76[.]11:53 (a server that, at the time of writing, does not expose any DNS service) and for each of the following queries, the destination IP address is changed to the succeeding address, as shown in Figure 11.

The 180.76.76.0/24 network is owned by Baidu, and interestingly, some of the servers at these IP addresses do expose DNS services, such as 180.76.76.76, which is Baidu’s public DNS service.

We believe that when the DNS query packets are intercepted, the network implant forwards them to the attackers’ server. The implant can easily filter the packets by combining several values to create a fingerprint, for instance:

- destination IP address

- UDP port (we observed 53, 4499, and 8000),

- transaction ID of the DNS query matching 0xFEAD,

- domain name, and,

- DNS query with extraneous data appended.

Final thoughts

Using the attackers’ AitM capability to intercept packets is a clever way to hide the location of their C&C infrastructure. We have observed victims located outside of China – that is, in Japan and the United Kingdom – against whom the orchestrator was able to deploy the backdoor. The attackers then sent commands to the backdoor to download plugins; for example, the victim from the UK received two plugins designed to collect information and chats from Tencent QQ. Therefore, we know that the AitM system was in place and working, and we must assume that the exfiltration mechanism was as well.

Some of the servers – for instance, in the 180.76.76.0/24 network – seem to be anycasted, meaning that there might be multiple servers geolocated around the world to reply to (legitimate) incoming requests. This suggests network interception is likely performed closer to the targets rather than closer to Baidu’s network. Interception from a Chinese ISP is also unlikely because Baidu has part of its network infrastructure outside of China, so victims outside China may not go through any Chinese ISPs to reach Baidu services.

NSPX30

In the following sections we will describe the major stages of execution of the malware.

Stage 1

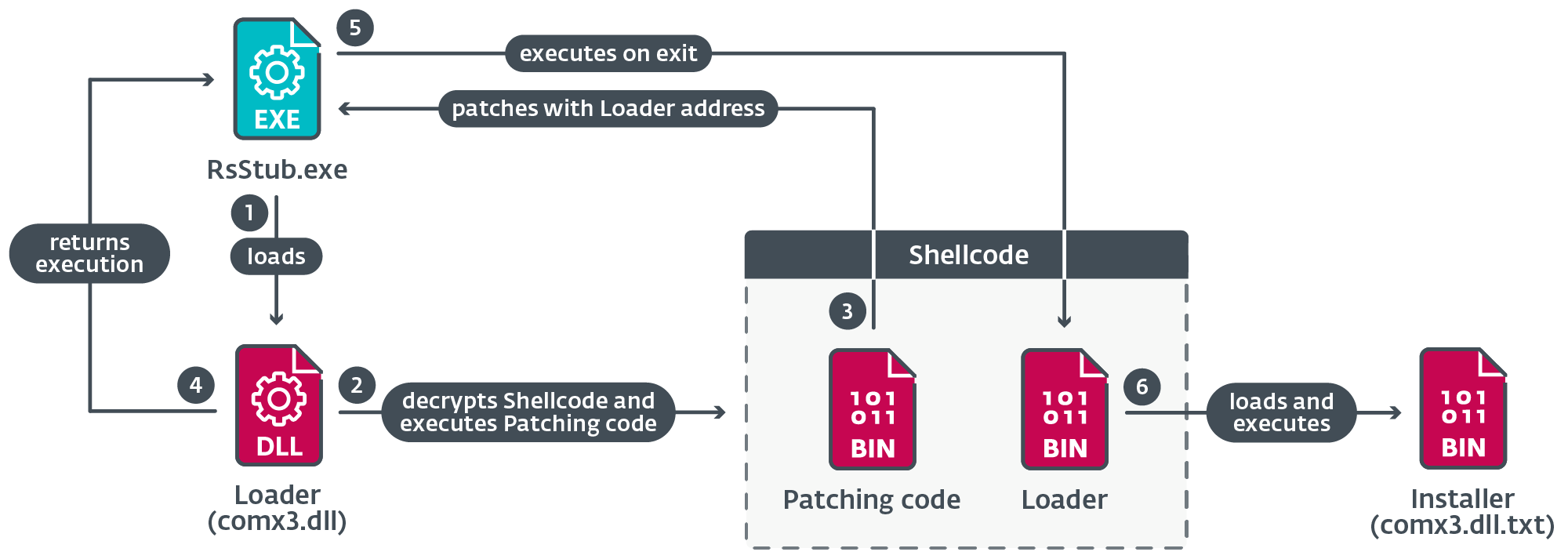

Figure 12 illustrates the execution chain when the legitimate component loads a malicious dropper DLL that creates several files on disk.

The dropper executes RsStub.exe, a legitimate software component of the Chinese antimalware product Rising Antivirus, which is abused to side-load the malicious comx3.dll.

Figure 13 illustrates the major steps taken during the execution of this component.

When RsStub.exe calls ExitProcess, the loader function from the shellcode is executed instead of the legitimate API function code.

The loader decrypts the installer DLL from the file comx3.dll.txt; the shellcode then loads the installer DLL in memory and calls its entry point.

Installer DLL

The installer uses UAC bypass techniques taken from open-source implementations to create a new elevated process. Which one it uses depends on several conditions, as seen in Table 3.

Table 3. Main condition and respective sub-conditions that must be met in order to apply a UAC bypass technique

The conditions verify the presence of two processes: we believe that avp.exe is a component of Kaspersky’s antimalware software, and rstray.exe a component of Rising Antivirus.

The installer attempts to disable the submission of samples by Windows Defender, and adds an exclusion rule for the loader DLL msnsp.dll. It does this by executing two PowerShell commands through cmd.exe:

- cmd /c powershell -inputformat none -outputformat none -NonInteractive -Command Set-MpPreference -SubmitSamplesConsent 0

- cmd /c powershell -inputformat none -outputformat none -NonInteractive -Command Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath “C:\Program Files (x86)\Common Files\microsoft shared\TextConv\msnsp.dll”

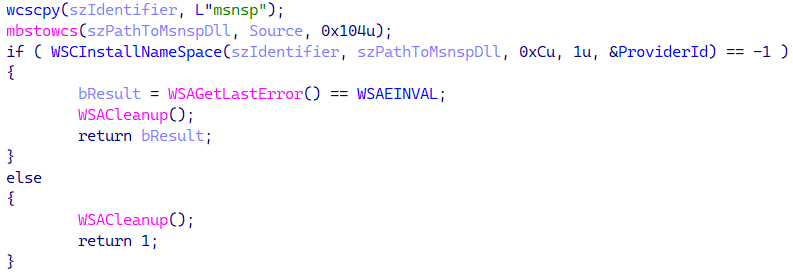

The installer then drops the persistent loader DLL to C:\Program Files (x86)\Common Files\microsoft shared\TextConv\msnsp.dll and establishes persistence for it using the API WSCInstallNameSpace to install the DLL as a Winsock namespace provider named msnsp, as shown in Figure 14.

As a result, the DLL will be loaded automatically whenever a process uses Winsock.

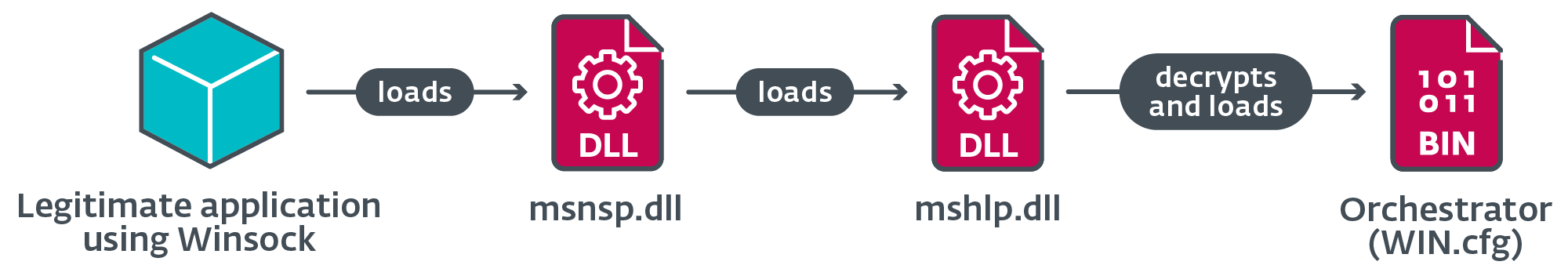

Finally, the installer drops the loader DLL mshlp.dll and the encrypted orchestrator DLL WIN.cfg to C:\ProgramData\Windows.

Stage 2

This stage begins with the execution of msnsp.dll. Figure 15 illustrates the loading chain in Stage 2.

Orchestrator

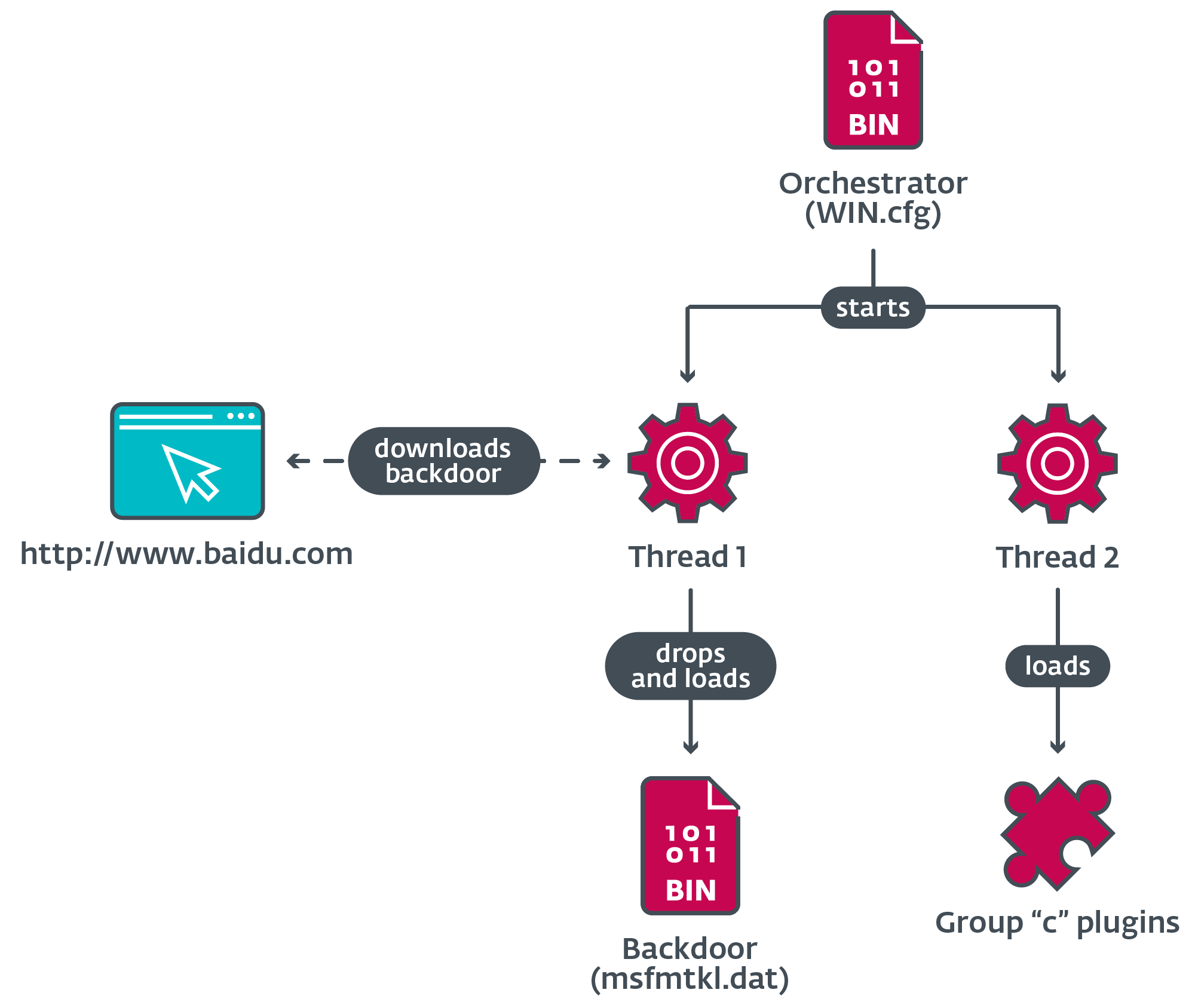

Figure 16 illustrates the major tasks carried out by the orchestrator, which includes obtaining the backdoor and loading plugins.

When loaded, the orchestrator creates two threads to perform its tasks.

Orchestrator thread 1

The orchestrator deletes the original dropper file from disk, and tries to load the backdoor from msfmtkl.dat. If the file does not exist or fails to open, the orchestrator uses Windows Internet APIs to open a connection to the legitimate website of the Chinese company Baidu as explained previously.

The response from the server is saved to a temporary file subject to a validation procedure; if all conditions are met, the encrypted payload that is inside the file is written to a new file and renamed as msfmtkl.dat.

After the new file is created with the encrypted payload, the orchestrator reads its contents and decrypts the payload using RC4. The resulting PE is loaded into memory and its entry point is executed.

Orchestrator thread 2

Depending on the name of the current process, the orchestrator performs several actions, including the loading of plugins, and addition of exclusions to allowlist the loader DLLs in the local databases of three antimalware software products of Chinese origin.

Table 4 describes the actions taken when the process name matches that of a security software suite in which the orchestrator can allowlist its loaders.

Table 4. Orchestrator actions when executing in a process with the name of specific security software

|

Process name |

Targeted software |

Action |

|

qqpcmgr.exe qqpctray.exe qqpcrtp.exe |

Attempts to load the legitimate DLL <CURRENT_DIRECTORY>\TAVinterface.dll to use the exported function CreateTaveInstance to obtain an interface. When calling a second function from the interface, it passes a file path as a parameter. |

|

|

360safe.exe 360tray.exe |

Attempts to load the legitimate DLL <CURRENT_DIRECTORY>\deepscan\cloudcom2.dll to use the exported functions XDOpen, XDAddRecordsEx, and XDClose, it adds a new entry in the SQL database file speedmem2.hg. |

|

|

360sd.exe |

Attempts to open the file <CURRENT_DIRECTORY>\sl2.db to adds a base64-encoded binary structure that contains the path to the loader DLL. |

|

|

kxescore.exe kxetray.exe |

Attempts to load the legitimate DLL <CURRENT_DIRECTORY>\security\kxescan\khistory.dll to use the exported function KSDllGetClassObject to obtain an interface. When it calls one of the functions from the vtable, it passes a file path as a parameter. |

Table 5 describes the actions taken when the process name matches that of selected instant-messaging software. In these cases, the orchestrator loads plugins from disk.

Table 5. Ochestrator actions when executing in a process with the name of specific instant-messaging software

|

Process name |

Targeted software |

Action |

|

qq.exe |

Attempts to create a mutex named GET QQ MESSAGE LOCK <PROCESS_ID>. If the mutex does not already exist, it loads the plugins c001.dat, c002.dat, and c003.dat from disk. |

|

|

wechat.exe |

Loads plugin c006.dat. |

|

|

telegram.exe |

Loads plugin c007.dat. |

|

|

skype.exe |

Loads plugin c003.dat. |

|

|

cc.exe |

Unknown; possibly CloudChat. |

|

|

raidcall.exe |

||

|

yy.exe |

Unknown; possibly an application from YY social network. |

|

|

aliim.exe |

Loads plugin c005.dat. |

After completing the corresponding actions, the thread returns.

Plugins group “c”

From our analysis of the orchestrator code, we understand that at least six plugins of the “c” group might exist, of which only three are known to us at this time.

Table 6 describes the basic functionality of the identified plugins.

Table 6. Description of the plugins from group “c”

|

Plugin name |

Description |

|

c001.dat |

Steals information from QQ databases, including credentials, chat logs, contact lists, and more. |

|

c002.dat |

Hooks several functions from Tencent QQ’s KernelUtil.dll and Common.dll in the memory of the QQ.exe process, enabling interception of direct and group messages, and SQL queries to databases. |

|

c003.dat |

Hooks several APIs: – CoCreateInstance – waveInOpen – waveInClose – waveInAddBuffer – waveOutOpen – waveOutWrite – waveOutClose This enables the plugin to intercept audio conversations in several processes. |

Backdoor

We have already shared several details on the basic purpose of the backdoor: to communicate with its controller and exfiltrate collected data. Communication with the controller is mostly based around writing plugin configuration data into an unencrypted file named license.dat, and invoking functionality from loaded plugins. Table 7 describes the most relevant commands handled by the backdoor.

Table 7. Description of some of the commands handled by the backdoor

|

Command ID |

Description |

|

0x04 |

Creates or closes a reverse shell and handles input and output. |

|

0x17 |

Moves a file with paths provided by the controller. |

|

0x1C |

Uninstalls the implant. |

|

0x1E |

Collects file information from a specified directory, or collects drive’s information. |

|

0x28 |

Terminates a process with a PID given by the controller. |

Plugin groups “a” and “b”

The backdoor component contains its own embedded plugin DLLs (see Table 8) that are written to disk and give the backdoor its basic spying and information-collecting capabilities.

Table 8. Descriptions of plugin groups “a” and “b” embedded in the backdoor

|

Plugin name |

Description |

|

a010.dat |

Collects installed software information from the registry. |

|

b010.dat |

Takes screenshots. |

|

b011.dat |

Basic keylogger. |

Conclusion

We have analyzed attacks and capabilities from a threat actor that we have named Blackwood, which has carried out cyberespionage operations against individuals and companies from China, Japan, and the United Kingdom. We mapped the evolution of NSPX30, the custom implant deployed by Blackwood, all the way back to 2005 to a small backdoor we’ve named Project Wood.

Interestingly, the Project Wood implant from 2005 appears to be the work of developers with experience in malware development, given the techniques implemented, leading us to believe that we are yet to discover more about the history of the primordial backdoor.

For any inquiries about our research published on WeLiveSecurity, please contact us at threatintel@eset.com.

ESET Research offers private APT intelligence reports and data feeds. For any inquiries about this service, visit the ESET Threat Intelligence page.

IOCs

Files

|

SHA-1 |

Filename |

ESET detection name |

Description |

|

625BEF5BD68F75624887D732538B7B01E3507234 |

minibrowser_shell.dll |

Win32/Agent.AFYI |

NSPX30 initial dropper. |

|

43622B9573413E17985B3A95CBE18CFE01FADF42 |

comx3.dll |

Win32/Agent.AFYH |

Loader for the installer. |

|

240055AA125BD31BF5BA23D6C30133C5121147A5 |

msnsp.dll |

Win32/Agent.AFYH |

Persistent loader. |

|

308616371B9FF5830DFFC740318FD6BA4260D032 |

mshlp.dll |

Win32/Agent.AFYH |

Loader for the orchestrator. |

|

796D05F299F11F1D78FBBB3F6E1F497BC3325164 |

comx3.dll.txt |

Win32/TrojanDropper.Agent.SWR |

Decrypted installer. |

|

82295E138E89F37DD0E51B1723775CBE33D26475 |

WIN.cfg |

Win32/Agent.AFYI |

Decrypted orchestrator. |

|

44F50A81DEBF68F4183EAEBC08A2A4CD6033DD91 |

msfmtkl.dat |

Win32/Agent.VKT |

Decrypted backdoor. |

|

DB6AEC90367203CAAC9D9321FDE2A7F2FE2A0FB6 |

c001.dat |

Win32/Agent.AFYI |

Credentials and data stealer plugin. |

|

9D74FE1862AABAE67F9F2127E32B6EFA1BC592E9 |

c002.dat |

Win32/Agent.AFYI |

Tencent QQ message interception plugin. |

|

8296A8E41272767D80DF694152B9C26B607D26EE |

c003.dat |

Win32/Agent.AFYI |

Audio capture plugin. |

|

8936BD9A615DD859E868448CABCD2C6A72888952 |

a010.dat |

Win32/Agent.VKT |

Information collector plugin. |

|

AF85D79BC16B691F842964938C9619FFD1810C30 |

b011.dat |

Win32/Agent.VKT |

Keylogger plugin. |

|

ACD6CD486A260F84584C9FF7409331C65D4A2F4A |

b010.dat |

Win32/Agent.VKT |

Screen capture plugin. |

Network

|

IP |

Domain |

Hosting provider |

First seen |

Details |

|

104.193.88[.]123 |

www.baidu[.]com |

Beijing Baidu Netcom Science and Technology Co., Ltd. |

2017‑08‑04 |

Legitimate website contacted by the orchestrator and backdoor components to download payloads. The HTTP GET request is intercepted by AitM. |

|

183.134.93[.]171 |

dl_dir.qq[.]com |

IRT‑CHINANET‑ZJ |

2021‑10‑17 |

Part of the URL from where the dropper was downloaded by legitimate software. |

MITRE ATT&CK techniques

This table was built using version 14 of the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

|

Tactic |

ID |

Name |

Description |

|

Resource Development |

Develop Capabilities: Malware |

Blackwood used a custom implant called NSPX30. |

|

|

Initial Access |

Supply Chain Compromise |

NSPX30’s dropper component is delivered when legitimate software update requests are intercepted via AitM. |

|

|

Execution |

Command and Scripting Interpreter: PowerShell |

NSPX30’s installer component uses PowerShell to disable Windows Defender’s sample submission, and adds an exclusion for a loader component. |

|

|

Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell |

NSPX30’s installer can use cmd.exe when attempting to bypass UAC. NSPX30’s backdoor can create a reverse shell. |

||

|

Command and Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic |

NSPX30’s installer can use VBScript when attempting to bypass UAC. |

||

|

Native API |

NSPX30’s installer and backdoor use CreateProcessA/W APIs to execute components. |

||

|

Persistence |

Hijack Execution Flow |

NSPX30’s loader is automatically loaded into a process when Winsock is started. |

|

|

Privilege Escalation |

Event Triggered Execution |

NSPX30’s installer modifies the registry to change a media button key value (APPCOMMAND_LAUNCH_APP2) to point to its loader executable. |

|

|

Abuse Elevation Control Mechanism: Bypass User Account Control |

NSPX30’s installer uses three techniques to attempt UAC bypasses. |

||

|

Defense Evasion |

Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information |

NSPX30’s installer, orchestrator, backdoor, and configuration files are decrypted with RC4, or combinations of bitwise and arithmetic instructions. |

|

|

Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools |

NSPX30’s installer disables Windows Defender’s sample submission, and adds an exclusion for a loader component. NSPX30’s orchestrator can alter the databases of security software to allowlist its loader components. Targeted software includes: Tencent PC Manager, 360 Safeguard, 360 Antivirus, and Kingsoft AntiVirus. |

||

|

Indicator Removal: File Deletion |

NSPX30 can remove its files. |

||

|

Indicator Removal: Clear Persistence |

NSPX30 can remove its persistence. |

||

|

Indirect Command Execution |

NSPX30’s installer executes PowerShell through Windows’ Command Shell. |

||

|

Masquerading: Match Legitimate Name or Location |

NSPX30’s components are stored in the legitimate folder %PROGRAMDATA%\Intel. |

||

|

Modify Registry |

NSPX30’s installer can modify the registry when attempting to bypass UAC. |

||

|

Obfuscated Files or Information |

NSPX30’s components are stored encrypted on disk. |

||

|

Obfuscated Files or Information: Embedded Payloads |

NSPX30’s dropper contains embedded components. NSPX30’s loader contains embedded shellcode. |

||

|

System Binary Proxy Execution: Rundll32 |

NSPX30’s installer can be loaded through rundll32.exe. |

||

|

Credential Access |

Adversary-in-the-Middle |

The NSPX30 implant is delivered to victims through AitM attacks. |

|

|

Credentials from Password Stores |

NSPX30 plugin c001.dat can steal credentials from Tencent QQ databases. |

||

|

Discovery |

File and Directory Discovery |

NSPX30’s backdoor and plugins can list files. |

|

|

Query Registry |

NSPX30 a010.dat plugin collects various information of installed software from the registry. |

||

|

Software Discovery |

NSPX30 a010.dat plugin collects information from the registry. |

||

|

System Information Discovery |

NSPX30’s backdoor collects system information. |

||

|

System Network Configuration Discovery |

NSPX30’s backdoor collects various network adapter information. |

||

|

System Network Connections Discovery |

NSPX30’s backdoor collects network adapter information. |

||

|

System Owner/User Discovery |

NSPX30’s backdoor collects system and user information. |

||

|

Collection |

Input Capture: Keylogging |

NSPX30 plugin b011.dat is a basic keylogger. |

|

|

Archive Collected Data: Archive via Library |

NSPX30 plugins compress collected information using zlib. |

||

|

Audio Capture |

NSPX30 plugin c003.dat records input and output audio streams. |

||

|

Automated Collection |

NSPX30’s orchestrator and backdoor automatically launch plugins to collect information. |

||

|

Data Staged: Local Data Staging |

NSPX30’s plugins store data in local files before exfiltration. |

||

|

Screen Capture |

NSPX30 plugin b010.dat takes screenshots. |

||

|

Command and Control |

Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols |

NSPX30’s orchestrator and backdoor components download payloads using HTTP. |

|

|

Application Layer Protocol: DNS |

NSPX30’s backdoor exfiltrates the collected information using DNS. |

||

|

Data Encoding: Standard Encoding |

Collected data for exfiltration is compressed with zlib. |

||

|

Data Obfuscation |

NSPX30’s backdoor encrypts its C&C communications. |

||

|

Non-Application Layer Protocol |

NSPX30’s backdoor uses UDP for its C&C communications. |

||

|

Proxy |

NSPX30’s communications with its C&C server are proxied by an unidentified component. |

||

|

Exfiltration |

Automated Exfiltration |

When available, NSPX30’s backdoor automatically exfiltrates any collected information. |

|

|

Data Transfer Size Limits |

NSPX30’s backdoor exfiltrates collected data via DNS queries with a fixed packet size. |

||

|

Exfiltration Over Alternative Protocol: Exfiltration Over Unencrypted Non-C2 Protocol |

NSPX30’s backdoor exfiltrates the collected information using DNS. |