Africa Tackles Online Disinformation Campaigns During Major Election Year

A dramatic increase in online disinformation attacks against African nations and international agencies operating on the continent has information security and cybersecurity specialists scrambling to find solutions to the ballooning problem.

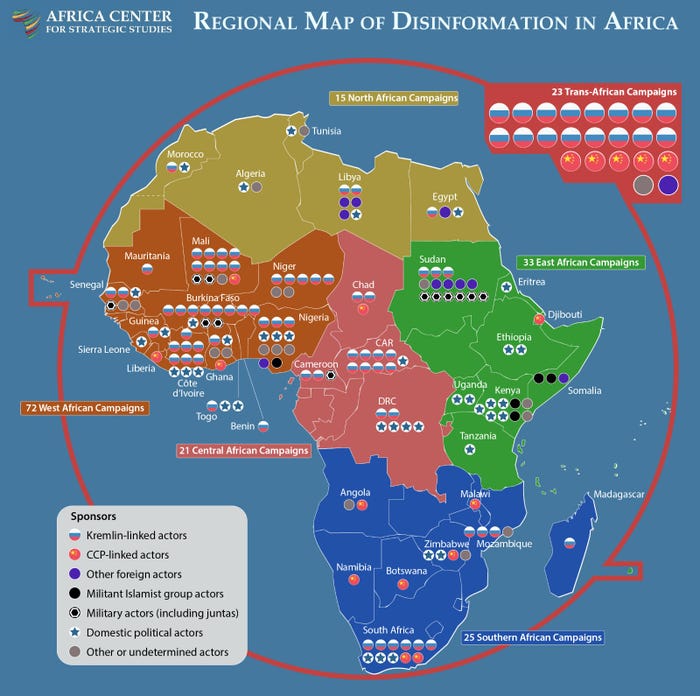

In 2023, Africa saw at least 189 documented disinformation campaigns, about four times the number reported the previous year, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies at the National Defense University, an academic institution within the US Department of Defense. The surge in attacks comes as at least 18 African nations are set to hold elections in the coming year, according to a report in The Economist, making disinformation a key threat for existing governments and businesses that rely on stable economies.

As these threats spread, cybersecurity professionals should seek protection strategies — but not expect to find a single solution to the problem, says Mark Duerksen, a research associate with the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

“Disinformation is not just a technical problem but is also a social and political question that will involve layered responses to build resilience, so the work of cyber experts can only be part of the solution,” Duerksen says. “However, we are seeing increasingly sophisticated disinformation campaigns that leverage cyberattacks to amplify, launder, and stoke disinformation.”

The 50-plus countries on the continent this year continue to improve their cybersecurity postures, if unevenly. A number of institutions, such as the University of Lagos and Shehacks Ke, are aiming to improve cybersecurity talent in the region, but many countries continue to lag behind in cyber hygiene.

Mainly Foreign Influence Operations

While disinformation is a worldwide problem, Africa has become a significant target for both state-sponsored disinformation and domestic campaigns, according to a recent report by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies. Foreign governments account for the majority of disinformation campaigns, with about 60% of campaigns discovered in 2023 attributed to Russia, China, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, according to the report.

More than 189 disinformation attacks targeted African nations in 2023. Source: Africa Center for Strategic Studies

Of the 23 campaigns targeting not just one country but entire African regions, 16 came from groups linked to Russia. Russia is also behind a plurality of 189 attacks against countries on the continent, especially in western Africa, following the withdrawal of French troops from Mali and other nations in the the Sahel, according to a report by the policy think tank Atlantic Council and the Digital Forensics Research Lab (DFRLab).

The report points to the example of Russia invading Ukraine. At the time, the social media accounts of a number of Nigerian journalists were hacked and used to spread pro-Putin hashtags as well as false information, creating an impression of African support for Russia, Duerksen says.

Currently, there are 600 million Internet users — 400 million of which are active social media users — in Africa. African citizens are some of the most voracious users of social-media platforms, with users in Nigeria and Kenya among those Internet-enable individuals spending the most time on social media. Overall, Internet penetration rates vary, from 7% in the Central African Republic to 51% in Nigeria, according to the Atlantic Council/DFRLab report.

Protecting citizens and businesses from disinformation campaigns requires a plethora of initiatives, from supporting local journalism and media literacy to improving cybersecurity for elections and detecting, reporting, and removing networks of inauthentic social-media users, according to a recent report, “Countering Disinformation Effectively: An Evidence-Based Policy Guide” by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Focus on User-Centric Security

While some experts question whether disinformation campaigns fall within the cybersecurity professionals’ purview, most place the topic in the holistic discipline of human-centered security along with creating effective security warnings for users and hardening employees against sophisticated phishing attacks.

“One key takeaway is the need to develop the ability to track and analyze disinformation through decentralized yet interoperable approaches and to set up ISACs — information sharing and analysis centers, a concept that comes directly from cybersecurity — as hubs for counter-disinformation,” Duerksen says. “Progress is being made in creating standardized frameworks and definitions so that researchers can share datasets and collectively piece together the actors and tactics behind the sprawling disinformation campaigns we’re starting to see.”

Cybersecurity experts who work with government agencies should study the threat of disinformation, he says. Just like anti-phishing training, media literacy education can help make the workforce more resilient against attacks.

“This means developing situational awareness of emerging digital information spaces proactively rather than waiting for something to happen,” Duerksen says. “Having a response plan in place — that includes a strategic communications playbook and contacting social media companies — for if and when a disinformation attack happens may seem overly cautious now, but companies are learning the hard way how fast and damaging to their reputations and bottoms lines these kinds of attacks can be when they happen.”